With the latest polls suggesting a likely victory for the Democrats in the November U.S. presidential elections, a looming foreign policy crisis awaits a potential Biden administration: escalating tensions with Iran. The Democrats have already vowed to abandon Washington’s current “maximum pressure” policy against Tehran — what they refer to as the “Trump administration’s race to war with Iran” — and return to the 2015 nuclear agreement, which the U.S. walked away from in 2018. Joe Biden himself recently asserted that he would not only “rejoin the [2015] agreement,” but would use the deal as a “starting point for follow-on negotiations.” In essence, this would be a return to the 2015 Obama-era Iran policy, centered on negotiations and a future deal with Tehran.

But while the Democrats’ “diplomacy first” approach has won praise across the Atlantic as the solution to deescalating tensions with Tehran, this Western-centric view ignores the changing reality on the ground in Iran. If Biden thinks he can return to the 2015 status quo, he may be in for a surprise. Crucially, there are three major differences in the current Iranian landscape from that of the Obama era, all of which could act as significant barriers to Biden’s proposed Iran policy and plans to reach a new agreement with Tehran.

Frequent unrest

The first of these changes relates to the Iranian streets. In the past three years, Iran has experienced continuous waves of anti-regime unrest — a clear sign that public sentiment toward the Islamic Republic has significantly changed. While there is little doubt that economic turmoil as a result of U.S. sanctions has contributed to internal dissent, homegrown problems — including rampant state corruption and increasing authoritarian repression — are the main drivers of domestic unrest. Protests have also been distinctively anti-regime in nature, as seen in the last nationwide demonstrations in November 2019, which saw the Islamic Republic’s security forces kill as many as 1,500 civilians in less than two weeks.

The growing trend of unrest in Iran shows that protests are not only getting bigger in size and scope, but the Islamic Republic’s response is also becoming more violent in nature. The human and economic consequences of COVID-19 will only accelerate this trend and it won’t be long until Iranians are back on the streets — something even regime insiders concede. Any future talks with Iran will take place against the backdrop of frequent unrest, which will be hard to ignore and put significant pressure on next U.S. administration to condemn any violence against the Iranian people.

Expansion of IRGC power

A contributing factor to the above is the expanding power of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the clerical regime’s ideological army. Up until now, Western policymakers have treated the IRGC as part of the Islamic Republic’s “deep state,” but the Guard now virtually operates as the state itself. The IRGC controls the Iranian Parliament in all but name and has set its eyes on the Iran’s presidency in the upcoming 2021 elections. The expansion of IRGC power — which is taking place with the blessing of Iran’s supreme leader — will not only accelerate Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s authoritarian push for domestic Islamization, but it will also increase Tehran’s investment in regional and international militancy. The new speaker of the Iranian Parliament, former IRGC commander Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, has already asserted that the legislature considers supporting designated terrorist groups like “Hezbollah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad [it’s] revolutionary and national duty” and has vowed to increase their power. Indeed, the clerical regime’s bond with Islamist militants across the Middle East is not just financial, it is also rooted in ideology — particularly groups that are closer to the IRGC. While Biden may seek to use sanctions relief as an incentive to convince Tehran to stop its support for terrorism, no amount of material reward will moderate the IRGC’s appetite for militancy — as the 2015 nuclear agreement demonstrated. The further militarization of the Islamic Republic at the behest of the IRGC will take place regardless of the outcome of the U.S. elections.

Supreme leader’s succession

But the biggest barrier to future diplomacy with Iran relates to timing and the issue of Khamenei’s succession. After 30 years of absolute rule, the 81-year-old ayatollah is preparing the foundations for a post-Khamenei Islamic Republic, unveiling his plans for the second phase of the Islamic Revolution in a manifesto that calls for “young and hezbollahi” (ideologically hardline) leadership across Iran’s branches of government as a way to ensure the continuation of his hardline Islamist vision.

Hostility toward the U.S. is central to Khamenei’s system of values and therefore its continuation is a key ingredient in ensuring his ideology outlives him. Donald Trump’s maximum pressure campaign may have accelerated this trend of hardline domination, but it was always going to happen anyway around the Khamenei succession. The ayatollah’s new generation of rising radicals has already declared there is “no difference” between Trump and Biden and outlined their opposition to future talks with Washington. For Tehran, the timing may simply not be right for an agreement with the U.S. And while Iran’s economy is in tatters, the ruling clergy will likely look eastwards toward Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping for a lifeline — two illiberal regimes that will among other things be indifferent to the Islamic Republic’s authoritarian practices, including its domestic human rights abuses.

Khamenei and IRGC will buy time

Going forward in the short term, and certainly before the U.S. elections in November, two aspects of Iranian positioning will be pronounced. First, Tehran will be overly careful not to escalate tensions with the U.S. that could turn into an open shooting war. That is the sort of combustible condition Tehran would find the most unwieldy. Second, the Iranians have been preparing their diplomatic messaging aimed at a possible Biden presidency, or even a re-elected Trump administration, by carefully avoiding any remobilization of international opinion against Tehran on the nuclear file and showing Washington to be the outlier in the Iran-U.S. conflict.

Most recently this Iranian circumspection has been evident in Tehran’s muted reaction to a major campaign of sabotage against sensitive targets in Iran. The number of sudden “accidents” at various points in the country suggested an orchestrated campaign of sabotage was under way. This campaign even hit the Natanz nuclear enrichment facility on July 2, by far the most significant given its strategic value. The Islamic Republic remained cryptic about its findings in regard to the culprits and did not admit to a deliberate act of sabotage until Aug. 23. Even so, Tehran has been largely restrained about pointing the finger given that this would necessitate retaliation, which is exactly the kind of escalation the Iranians want to avoid right now.

In reality, the Iranian leadership sees the sabotage as part of a coordinated American-Israeli campaign unleashed after the Trump administration and the Israelis concluded that the Islamic Republic will not change any of its policies while Trump is in the White House. The rationale, as Tehran sees it, is to set Iran’s nuclear and missile programs back as much as possible in case Trump loses in November. The Iranian leadership appears to believe there is one other likely reason why the U.S. and Israel have decided to act: To force the Iranians to kick out international nuclear inspectors on charges that they are passing sensitive information to the U.S. and Israeli intelligence services, which it believes makes such acts of sabotage at Iran’s nuclear sites possible. Not wanting to give Washington any pretexts, the Iranians opted instead to not only welcome the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Rafael Grossi, to Tehran on Aug. 24, but also provide the agency with additional access to suspected nuclear sites.

Tehran’s lack of retaliation has historic precedent. About 10 years ago, when the Americans and the Israelis used the Stuxnet computer virus to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program, Iran basically accepted the losses it incurred and simply continued its nuclear program as before. Its response to this latest sabotage campaign seems to be the same and Tehran will remain vigilant to present itself as the responsible party in the U.S.-Iran conflict at least on the nuclear file.

Driving a wedge between the US and Europe

But it would be a profound mistake to interpret such actions as being part of the Islamic Republic’s newfound desire to become a responsible global actor. Rather, it is part of Ayatollah Khamenei’s calculated, longer-term strategy to isolate and weaken Washington on the global stage, not least from its traditional ally, Europe. It has long been Khamenei’s goal to spilt Europe from the U.S. – the ayatollah’s so-called “West minus U.S.” policy. The cracks that have emerged between the U.S. and Europe over the 2015 nuclear agreement have at last provided Khamenei with an opportunity to implement this ambition. In turn, it has become explicitly clear to the Iranian leadership that Europe will continue to prioritize the 2015 nuclear deal above all other outstanding issues with Iran, such as its regional destabilization and IRGC terrorism.

This status-quo has, in many ways, provided Khamenei with the best of both worlds. On the one hand, by cooperating on the nuclear file, the Islamic Republic has been able to preserve its image in the eyes of the Europeans and make the Trump administration look like the rogue actor for abandoning the agreement. On the other, the priority Europe has given to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) has resulted in Brussels biting its tongue in relation to Iran’s malign activities that sit outside the deal, enabling Tehran to use other means to strike back at the U.S. and regional allies without condemnation. The lack of European response to consistent ballistic missile attacks on American positions in Iraq via Iranian-backed proxies, or Tehran’s alleged plot to assassinate the U.S. ambassador in South Africa, are prime examples — a scenario that would have been unimaginable before the JCPOA.

Indeed, the Islamic Republic has sought to leverage this status quo — namely, disdain for American unilateralism — to deepen the divide between U.S. and European interests over Iran to cause irreparable long-term damage to the West’s Iran policy, regardless of who wins the U.S. election in November 2020. In that regard, Iran’s regime is keen to build on some of the diplomatic defeats the Trump administration has suffered in recent weeks at the UN. For example, a UN report in July condemned the U.S. for the assassination of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard commander, Qassem Soleimani, despite Soleimani being on a UN blacklist for terrorism-related issues.

Likewise, on Aug. 14 Washington failed in its attempt to extend the U.N. arms embargo on Iran — which will expire on Oct. 18 — with European members of the U.N. Security Council (UNSC) opting to abstain despite their shared concern over the Islamic Republic’s access to weapons. The U.S. suffered another setback on Aug. 25, failing in its push at the UNSC to impose “snapback” sanctions on Iran.

Looking ahead

After more than 30 years of trying, the Islamic Republic’s ageing ayatollah may finally feel that he is on the road to detaching Europe from the U.S. on Iran policy. This is a trend Tehran wants to build on and hence, it is careful not to provide Washington with any pretext to seek a new international coalition against it.

The clerical regime’s biggest hope at the moment is that the weight of the international diplomatic opposition to Trump’s unilateralism will further isolate the U.S. and invariably force Washington — be it a second-term Trump administration or a Biden presidency — to significantly change course toward Tehran.

But while President Hassan Rouhani and his so-called “moderate” faction might claim that they seek “real” dialogue with Washington, the West should be careful not to misinterpret Tehran’s intent. As Rouhani himself conceded in a cabinet in a televised speech on June 24, the Khamenei-IRGC duet (the real powerbrokers in the Islamic Republic) are mainly interested in buying time and hedging. For them, extending a genuine olive branch to Washington, regardless of who the occupant of the White House is, does not at all appear to be in the cards.

Alex Vatanka is the Director of MEI’s Iran Program and a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Europe Initiative. Kasra Aarabi is a non-resident scholar with MEI's Iran Program and an analyst in the Extremism Policy Unit at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, where he works on Iran and Shi'a Islamist extremism. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

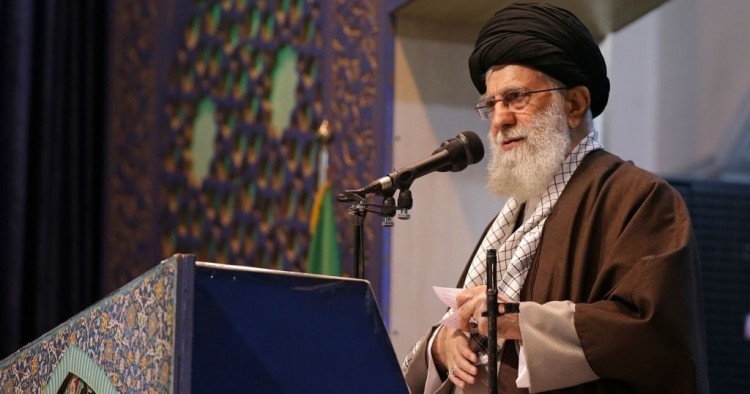

Photo by Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.